Real People, Real Jobs — Hanna Fahsholtz

An eighth grade teacher in the nation's second-largest school district

When I was in first grade, my teacher Ms. Savoy picked up on the fact that I couldn’t pronounce my R’s before even my parents did. Until then, I had skillfully avoided saying most words with the letter, including my own sister’s name. I initially resented my teacher for identifying an issue that required me to read in an office rather than play with my friends after school. But soon I felt relieved. I had a teacher who cared about me and wanted to help.

Later, on the first day of tenth grade, I sat in disbelief as my history teacher, Ms. de Grijs, announced that we would dedicate an entire unit to the Armenian Genocide, a piece of my family’s story that had been deliberately omitted from most school curriculums. I never thought my history was worthy of being taught in a classroom in the United States; Ms. de Grijs showed me otherwise.

For every year I was in school, I can point to at least one teacher who made a meaningful impact on how I viewed the world or myself (and in the case of Ms. Savoy, quite literally unlocked my voice). Teachers are some of the most important members of our workforce, and yet their work is greatly undervalued. At the same time, people are demonstrating less and less interest in the profession.

My friend Hanna is an exception. Over the last two years, I’ve watched with so much admiration as Hanna has evolved from being a student to leading a classroom full of them (and middle schoolers, no less). Now you get a glimpse into her life — and the realities of being a teacher — too.

Hanna Fahsholtz is an eighth grade English Language Arts (ELA) and Creative Writing Teacher at a Los Angeles Unified School District middle school. After college, she moved to Madrid, Spain to teach English through a Fulbright grant. Upon returning to LA, she joined the USC Center for Communication Leadership and Policy, where she served as Head Teaching Assistant for undergraduate and graduate journalism courses. These days, she juggles classroom life with grad school, finishing her M.Ed at UCLA.

In addition to many other systemic factors, I think teaching has such a high burnout rate partially because it’s difficult to understand what you’re signing up for.

On a workday in her life: Monday, April 28, 2025

My alarm goes off at 5:30 am. I hit the snooze button a dangerous number of times before dragging myself out of bed to turn on the tea kettle and shower. Because teaching consists of making a thousand micro-decisions per day, I try to limit the number of things I need to think about in the morning. I throw on the outfit I laid out the night before, eat the overnight oats waiting for me in the fridge, and grab my pre-packed lunch box. I check my phone as I pull out of the driveway, balancing my thermos of black tea between my knees — 6:35am. I’m running late.

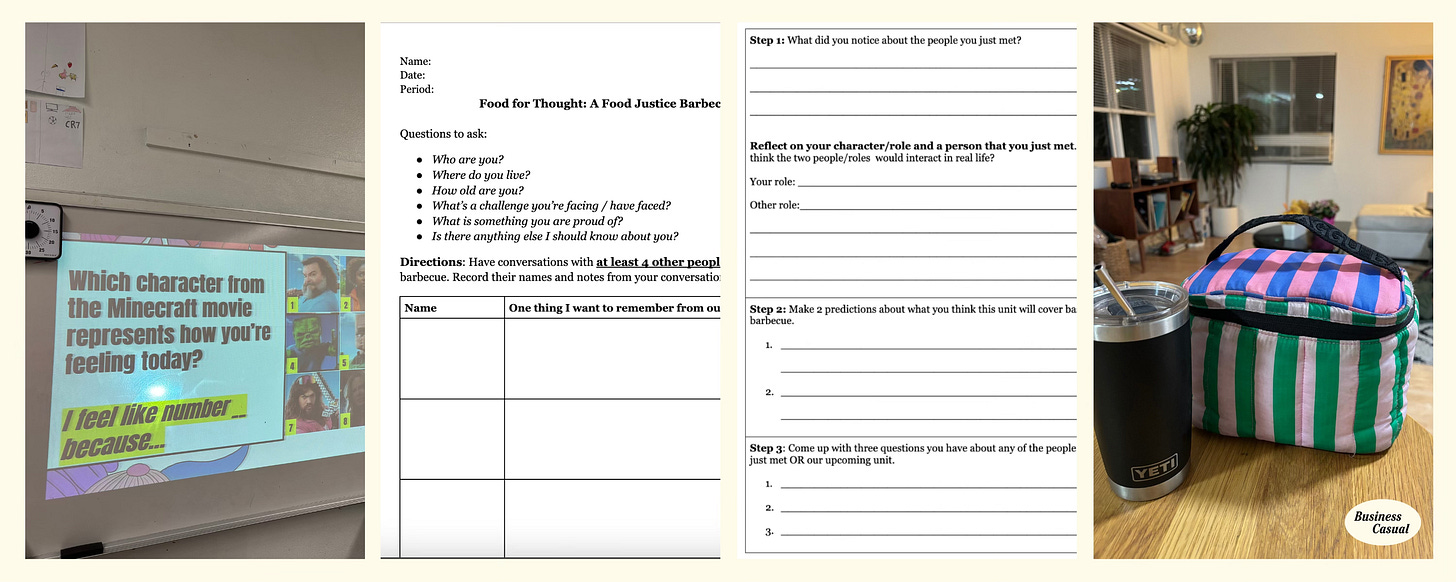

Luckily, I live about six minutes from my school — a luxury I don’t take for granted in a city where teachers often drive over an hour to get to school. Today, like most mornings, I make a beeline for the copy room. By 7:20, I’m in my classroom and around 7:45, the first students start to trickle in. I make a point of standing at the door to greet them before class starts, trying to convey how happy I am that they’re here even though I’m feeling tired. I’m nervous to see how they’ll react to today’s new role playing activity — a mixer “barbecue” that will introduce them to different aspects of food justice.

After the 8am bell rings and we finish the warmup, it takes 10 minutes of cajoling students to get them reading the mixer roles. For the most part, the mixer works and a few students made especially thoughtful comments at the end of the period. I’m feeling energized by this new unit.

At 9:35, students head out to nutrition. A few students from my next class come in early to hang out and play games on their Chromebooks. I chat with them as I pick up stray pencils and papers first period left (I still need to perfect my class exit routine) and tweak a few aspects of the lesson to make it run more smoothly for the next class.

Third period comes and goes, and again, class goes well. The mixer is a success! I’m on a high — this is NOT how I’m typically feeling about my lessons, but it seems like the extra hours I spent planning last night paid off.

At 11:26, the lunch bell rings and students leave. I spend the next 30 minutes eating lunch at my desk while trying to think of what to do today in Creative Writing. Some teachers eat together during lunch, but most days I’m too overstimulated to seek out more socializing during my break. I usually need this time to catch up on lesson planning anyways.

The bell rings again at 11:57, signaling the start of my prep period — I have 90 minutes each day to use as I please. Today, I find a lesson online to use next period. We will start writing poems about what students’ names mean to them. I don’t love the lesson, but it’ll have to be good enough for this week. Unfortunately, the stack of argumentative essays sitting in my “to grade” pile goes untouched yet again.

Seventh period starts at 1:32, and it goes pretty smoothly. Students enjoy talking about why their family chose their names, which nicknames they go by, and the personalities they associate with their names.

Students go home at 3:08, and I spend the next 20 minutes plugging in Chromebooks to the charging cart (a task I’ve learned students can’t be trusted to do) and sweeping the classroom. I stay at school until about 5, texting and calling parents about students who are missing assignments or won’t stop using their phones in class, and finishing my plans for tomorrow.

When I get home, I eat dinner, catch up with my roommate, and muster the energy to go for a short run. By 8pm, I’m crashing from yesterday’s late night. I prep my lunch, lay out my clothes for tomorrow, and am asleep by 9.

On a misconception people often hold about her job:

If you’re good with kids or excel at one-on-one tutoring, teaching will come naturally! (This is a misconception I, too, held until I stood in front of a classroom for the first time.) Although building individual relationships with students is critical, the skills you need to manage a classroom full of students are so different from what you need to work with students one-on-one. This year I’ve learned the hard way that learning cannot happen until basic classroom norms and routines are in place.

On something about her role that you wouldn’t know from the job description:

You have to be ruthlessly efficient with time management and prioritizing tasks. I’ve gotten really into productivity science since starting (although I have a long way to go).

On what someone who wants her job can do right now to get there:

I think the challenge is less “How do I get a teaching job?” and more “What can I do to test how much I enjoy the reality of teaching?” Schools will always need teachers, so the most important step you can take is figuring out if teaching is for you before investing the time, energy, and money it takes to become a teacher. In addition to many other systemic factors, I think teaching has such a high burnout rate partially because it’s difficult to understand what you’re signing up for. I recommend talking to current teachers and job shadowing one for the full school day if possible. Substitute teaching is also pretty much as close as you can get to the real deal before becoming a teacher and has a relatively low barrier to entry. If you’re at a place in your career where you can do this, programs like City Year and AmeriCorps offer year-long opportunities for college graduates to work in public schools.

If you decide teaching is right for you and have the means to do so, find the most supportive graduate program and school you can to prepare you. The support you have going into your first year can make the difference between loving your job and leaving the profession in June.

On her favorite part of her job:

The kids!!! Funniest, smartest, most creative people I’ve ever met. Even during the most challenging class periods, I laugh at least once when I’m not supposed to.

On the most challenging part of her job:

It’s a tie between feeling like there’s never enough time to do the things you need to do, and the lack of clear feedback or performance indicators you get on your work. At least for me and the other first-year teachers I talk to, questions like “Are my students actually learning? Did that lesson make sense? Are students going to retain anything from this class next year?” are constantly running through my head. My eighth graders are never going to tell me “Amazing lesson, Ms., I fully understood the concepts we discussed and feel confident about how to apply my learning outside of class.”

I’m still learning to exist in the ambiguity that comes from not knowing if what we do in class will ultimately matter to my students. One of my professors says that teaching is about “planting seeds”: we might not know if a lesson or class made a difference to students until years later.

On AI:

AI is endlessly useful for teachers. I use it as a translator to communicate with parents and translate materials for multilingual students, and to change texts to provide options for students with different reading levels.

I also use it for brainstorming lesson plans. When I have an idea of a lesson plan but need help refining it or generating components, I turn to AI. Caveat: based on what I’ve seen at this point, it cannot design a lesson from start to finish without me significantly editing the lesson plan. AI cannot know our students the way we do.

In my classroom, we do all of the writing for essays and assignments during class. My thinking behind this policy is that my students still need to build up their foundational writing skills and critical thinking. If they use AI at this point, I don’t see how they will develop the skills necessary to question or improve an AI-generated response. I’ve seen high school ELA teachers give students options to write an original essay or improve an AI-generated essay. These kinds of moves seem like effective ways to embrace the reality of AI for students while still pushing them to develop their critical thinking abilities.

I wish I had more guidance on how to use AI in the classroom — I would love to feel more confident about how to address situations when students use AI for their assignments.

On things she would change about how schools are run:

The first thing I would change is to meet students’ needs so that they can show up ready to learn. In my graduate coursework, we learned about how feeling unsafe shuts down most parts of the brain except the parts we need for survival, rendering it physically incapable of learning. Students legitimately cannot learn if these conditions — being fed, having access to healthcare and housing regardless of immigration status — are not met first. I’d also integrate social-emotional learning — such as how to regulate yourself when upset — into every part of the curriculum. The last thing I would change is to have ethnic studies — not watered down multicultural curriculum, but pedagogy for liberation — taught in every school.

In my fantasy alternate reality, schools as we know them don’t exist. Learning takes place outside (in nature whenever possible), in the real world. If I could apply this to our school systems today, learning should extend beyond school walls and offer students as many opportunities for real-world learning as possible. For example, partner with community organizations and have students work on projects with real audiences (not just their teachers). Make sure students aren’t just learning about world problems, but also what they can do to solve these problems and advocate for themselves and their communities. Fostering hope in students (rather than cynicism or despair) is essential.

One thing (tool, skill, secret, etc.) anyone who wants her job must know:

How to communicate strategically — no matter what you’re saying, you constantly need to convince students, parents, and other school staff that you are on the same team and want the same thing: the students’ success.

One person or publication you must follow if you want her job:

@the.unteachables and @teaching_to_a_riot: holistic approach to classroom management based on meeting student needs.

Also love Edutopia for excellent ideas related to all aspects of teaching.

Her work-life balance on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = works all the time, including weekends, and doesn’t have any personal free time; 10 = standard 9-5 job with manageable demands):

2, but hoping to get it more balanced after my first year of teaching! Also a little skewed by grad school.

Thanks for reading! Let me know who your favorite teacher was in the comments.